NHS homeopathy in the spotlight

Some people take the position that public money should not be spent on homeopathy because “there is no proof that it works” or “tax-payers money shouldn’t be spent on placebos”.

This is not an argument limited to the UK but is repeated across the world – especially in Europe – where homeopathy funding or rebates are available from national health budgets. Yet, very few people have access to the facts needed to weigh up this argument effectively

While NHS funding of homeopathy has now stopped in the UK, the points below highlight more general issues with the argument against public funding of homeopathy.

How much does homeopathy cost?

- In 2016, just £92,412 was spent on 40,000 homeopathy prescriptions from a total expenditure of £9.2 billion.1

- Out of the total NHS budget of £100 billion a year, roughly £4 million (0.004%) is spent annually on Homeopathy2 if you include everything from running the hospitals departments to paying the doctors.

When considering value for money, it should be remembered that if homeopathy patients were not treated with this service, they would have to be treated by other departments using more expensive conventional drugs.

Homeopathy should be considered in the same way as all other NHS treatments

Some people argue that the NHS should not pay for homeopathy because we do not know that it works, whereas conventional medical drugs are ‘tried and tested’. Surprisingly this issue isn’t actually as clear-cut as one might think.

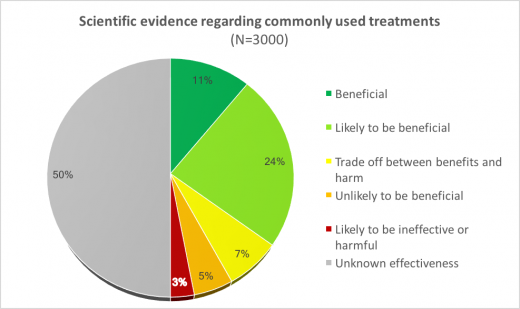

Analysis by the British Medical Journal’s (BMJ) Clinical Evidence3 shows that just 11% of 3,000 commonly used NHS treatments are known to be beneficial:

This data clearly indicates that the NHS pays for many treatments – besides homeopathy – for which the evidence is still unclear.

What evidence is there that homeopathy helps NHS patients?

Five published ‘observational studies’ carried out from 1999 to the present day have tracked the outcome of patients being treated at NHS homeopathic hospitals. These studies consistently show that patients improve clinically following homeopathic treatment (often from chronic, difficult to treat conditions); some also highlight areas of potential economic benefit for the NHS as a whole in terms of reduced prescribing of conventional drugs. For example:

The largest observational study at Bristol Homeopathic Hospital followed over 6,500 consecutive patients with over 23,000 attendances in a six-year period4. 70% of follow-up patients reported improved health; 50% reported major improvement.

The results of this 2005 Bristol study have been confirmed by a more recent observational study, published in 2016, involving an audit of just under 200 patients. The audit demonstrated that patients with long-term conditions who come under homeopathic care experience statistically significant improvements in their presenting symptoms and wellbeing.5

A 500-patient survey at the Royal London Homeopathic Hospital showed that many patients were able to reduce or stop conventional medication following homeopathic treatment.6

When assessing these clinical results, it is important to remember that NHS patients were usually referred for homeopathy because conventional medicine had failed to give satisfactory results, or conventional treatment was contra-indicated in their case. One has to ask, now that these homeopathy services are not available, who will treat these 40,000 people instead? How ethical was it to remove a service valued by patients, without being able to offer them a viable alternative treatment?

Interesting related research from France

Homeopathy is widely used in France and a major study – referred to as the ‘EPI3’ study – following 8559 patients attending GP practices was used to assess the effectiveness of homeopathic treatment.7 The authors of this study include Lucien Abenhaim – former French General Director of Health (Surgeon General) – and individuals from respected academic institutions such as the Institut Pasteur in Paris, University of Bordeaux and McGill University, Montreal.

Key findings of the EPI3 project:

- Upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) – patients treated by GPs trained in homeopathy did as well clinically as those treated with conventional medicine, but used fewer conventional drugs8 518 adults and children with URTIs who consulted GPs certified in homeopathy had similar clinical results to those treated by conventional GPs, but had significantly lower consumption of antibiotics (OR=0.43, CI: 0.27–0.68) and antipyretic/anti-inflammatory drugs (OR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.38–0.76).

- Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) – patients treated with homeopathy did as well clinically as those treated with conventional medicine, but used only half the amount of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and had fewer NSAID-related side effects9

1153 eligible patients with MSD were followed for 12 months, comparing groups who received homeopathy (N=371) or conventional medicine (CM; N=272), or a mixed approach involving both approaches (N=510). The twelve-month development of specific functional scores was identical for all groups (p > 0.05). After adjusting for propensity scores, NSAID use over 12 months was almost half in the homeopathy group (OR, 0.54; 95%CI, 0.38-0.78) as compared to the CM group; no statistically significant difference was found in the mixed group (OR, 0.81; 95% CI: 0.59-1.15). MSD patients seen by homeopathic physicians showed a similar clinical progression when less exposed to NSAID in comparison to patients seen in CM practice, with fewer NSAID-related adverse events and no loss of therapeutic opportunity. - Sleep, anxiety and depressive disorders (SADD) – Patients treated by certified homeopathic physicians were less likely to be prescribed psychotropic drugs.10 The EPI3 ‘SADD’ study involved 1572 patients diagnosed with sleep, anxiety and depressive disorders seeking treatment from physicians in general practice (GPs), with three different practice preferences: strictly conventional medicine (GP-CM), mixed complementary and conventional medicine (GP-Mx) and certified homeopathic physicians (GP-Ho). Psychotropic drugs were more likely to be prescribed by GP-CM (64%) than GP-Mx (55.4%) and GP-Ho (31.2%). The three groups of patients shared similar SADD severity in terms of comorbidities and quality of life.

- NHS Digital: NHS Prescription Cost Analysis 2016 [Link]

- Freedom of Information Act request to the Department of Health by the Faculty of Homeopathy. Cost was £11.89 million between 2005 and 2008.

- BMJ Clinical Evidence, Efficacy Categorisations. 2017. Available from http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/set/static/cms/efficacy-categorisations.html [Accessed 25 Sept 2017]

- Spence D, Thompson E A, Barron S J. Homeopathic treatment for chronic disease: a 6-year university-hospital outpatient observational study. J Altern Complement Med 2005; 5: 793-798 | PubMed

- Thompson E, Viksveen P, Barron S. A patient reported outcome measure in homeopathic clinical practice for long term conditions. Homeopathy, 2016; 105(4): 309-317 | PubMed

- Sharples F, van Haselen R, Fisher P. NHS patients’ perspective on complementary medicine. Complement Ther Med 2003; 11: 243-248 | PubMed

- Grimaldi-Bensouda, L. et al. Benchmarking the burden of 100 diseases: results of a nationwide representative survey within general practices. BMJ Open 1, e000215 (2011) | Full Text

- Grimaldi-Bensouda, L. et al. Management of upper respiratory tract infections by different medical practices, including homeopathy, and consumption of antibiotics in primary care: the EPI3 cohort study in France 2007-2008. PloS One 9, e89990 (2014). | Full Text

- Rossignol, M. et al. Impact of physician preferences for homeopathic or conventional medicines on patients with musculoskeletal disorders: results from the EPI3-MSD cohort. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 21, 1093–1101 (2012) | PubMed

- Grimaldi-Bensouda, L. et al. Who seeks primary care for sleep, anxiety and depressive disorders from physicians prescribing homeopathic and other complementary medicine? Results from the EPI3 population survey. BMJ Open, 2012; 2 | Full text

To download a PDF summary of this page click here.